Morning Writer

My first real gig in the news business was in 2019. The year of mass shooters. At least, that’s what it felt like. It went by like a whirlwind, but there’s one story that sticks with me, about a girl from Florida who went missing, was declared armed and dangerous, and set off a national manhunt. It doesn’t end like you think it will. Maybe you, reader, can help me understand it.

This job was a real meat grinder. Two former broadcast news producers—priests at the temple of shoveling coal for Satan—me, and a girl from New Jersey named Samantha would assemble at 5:30 a.m. Monday through Friday on the 8th floor of a glass and steel monstrosity on Astor Place, right above the massive cube that kids and tourists like to whirl around.

That’s a hellishly early hour, but I was trying hard to get my career together and the job paid okay. So I’d wake up at 4:30 a.m., on a mattress on the floor of a basement in Williamsburg, to the tinkling of electronic chimes, the gentlest alarm I could find. I’d rub the sleep out of my eyes and sip enough coffee to start moving, and then I’d be off onto the cold Brooklyn street in the darkness, wrapping my heavy coat around me.

As I waited for the L train, construction dust from the work done overnight floated past the platform, ghostly and probably cancerous. I’d take my pick of seats on the train and meditate silently between Metropolitan Avenue and Union Square on how much I hated waking up before dawn. The graffitied pillars and walls of the subway tunnels flashed in my bleary vision like a darkened flipbook. On the later days of the week, my fellow travelers were coming in from a long night out, sometimes sleeping, sometimes cradling their head in their hands with a puddle of puke between their feet.

I’d hop out at Union Square and walk briskly to our office. I’d scan my card and pop out onto the 8th floor, where the others sat huddled around computer monitors. Around us, the city was dark and still and we could see the brilliant multitude of lights through the floor-to-ceiling windows. We were always the first ones there.

Following the Shooter

On those early mornings in the dark, with the lights of the city all around us or the sun just barely coming up over the Lower East side, we’d sit in front of an application called DataMinr, a sort of aggregated international police scanner meets Twitter feed. Events all over the world would flash on screen. Celebrity breakup. Economic Sanctions on Iran. Quadruple Murder in Rural Pennsylvania. Blow Away Bouncy House.

My boss loved Blow Away Bouncy House. “There’s two types of stories that do amazing for us,” he murmured to me. “Kidnapped ballerinas, and blow away bouncy houses.”

So we’d wait for something gruesome to pop up, and my boss would go “Ah-ha!” and we’d jump on it, finding the names of the victim’s family members, the local police department, using Google Maps and property records to find neighbors who might have witnessed whatever carnage we were covering. We’d use dubious databases like TRACERS and TLO, and call through cell phone numbers.

It might look something like this, looking for John Bergman.

“Hi, John?”

“Huh?”

*Click*

I’d try a different number.

“Hi, John?”

“No!”

*Click*

I’d try a different number.

”Hi, John?”

“Yes, hello?”

“Hi John, this is Mac with CBH news. So sorry to bother you right now…”

Then, the sales pitch would begin. The real key though, was with the guilty and the assailed. I don’t know if it represents a larger trend in the data, but that year we covered endless mass shootings. Always, the family of the victims and the family of the shooter were the best gets.

The victim's family was one thing. If they picked up the phone crying, they already knew. And that was okay. You’d whisper your condolences. “Who is handling media for the family?” and they’d tell you, or they tell you they didn’t know. At least half the time, you’d ask them if they’d heard the bad news about Jimmy, and they’d go, “What bad news?” and you’d have to sigh and tell them. I broke a lot of bad news.

But the family of the shooter, that’s where I really shone. “Hi there,” I’d say. “This is Mac with CBH News.” Then, the cincher. “How are you holding up?” Silence. A lot of people, particularly blue-collar men, haven’t ever been asked how they are feeling about anything ever. Sometimes the floodgates would open up. Confessions. Childhood trauma. He was a good kid. He didn’t mean it. Please don’t write anything bad about us.

Sometimes though, like a guy whose two toddler sons had been crushed to death by a falling tree in the back of his car, they’d just howl, wordless animal noises.

Maybe you think badly of me for doing this work, and maybe you should. All I can say is that I was young and desperate and didn’t know any better. All I wanted was to get through the day and pay my rent. Maybe I should have done a coding bootcamp instead.

The bigger picture though, is that this is how the sausage gets made in breaking news. Every time a major news story happens—a shooting, a plane crash, a celebrity debacle—every aunt, uncle, friend, old roommate, and neighbor is likely to be swarmed with phone calls from producers at CNN and NBC and FOX, like a biblical horde of locusts. “Hi Shane, this is Rebekkah with CNN. “ “So sorry to bother you, Deborah, this is Sam with The Daily Beast.” This is how the stories you read get made, without respect and without decorum. For that glorious year though, we were just quicker on the trigger.

The Dissolved Girl

Here’s the story that sticks with me through all this time.

In the spring of 2019, there was a nationwide manhunt for a girl named Sol Pais. Sol was an 18-year-old goth girl with a pinched, elfin face. In the selfies that the media ran of her, she looked pretty, with thin drawn-on-eyebrows, looking down her long nose at the camera with patrician contempt. In the class photos and surveillance pictures from Denver International Airport that ran later, after the story was finished, she looked confused and anorexia-skeletal.

Sol Pais stepped out of her parent’s house in the Miami suburb of Surfside on the sunny morning of April 15th and never came back. The next day, her parents called the cops, who got on her email and social media. They found an extensive online footprint, almost entirely dedicated to the worship of Columbine shooters Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, along with a one-way ticket to Denver and inquiries about how to buy a gun in Colorado. Sol’s parents reported her missing on April 16th. The famous Columbine shooting? April 20th.

It wasn’t hard to put two and two together. This Columbine-obsessed teen was headed to the site of the original crime, to do it again. So the authorities started a national manhunt and plastered her best selfies all over the news, and schools all over Colorado shut down, in fear of this young woman from Miami Beach with a gun and an obsession with school shooters. For their part, the FBI was calling Sol Pais “Armed and Dangerous.”.

In fact, Sol Pais was part of a bizarre internet subculture that sprang up in the wake of the Columbine shooting. Sometimes referred to as “Columbiners,” they were devotees of the shooters Klebold and Harris. Some bring guns to their schools and wreak their own horror. Others create and share affectionately drawn anime-style cartoons of the two shooters. It’s fair to describe it as a sort of online fandom.

If you were a grave-digging online investigator like me, you were all over it, parsing through her social media pages, calling her neighbors and relatives, members of her dad’s beach-rock band. One old lady who lived across the street from Sol’s family told me she was a nice girl, very quiet.

But as was often the case with quick-moving and “very online” stories, the anonymous frog-faced hordes of Twitter and 4chan were way ahead of us, doing work that would make State Department intelligence analysts green with envy. By the time I was getting behind my desk, the spring sun rising over the city, the internet sleuths had already dug up her spooky early 2000’s style NeoCities page, which was filled with gothy lyrics and hidden links.

“Keep an eye out for secret pages…” it prompted, in italicized purple-on-black font.

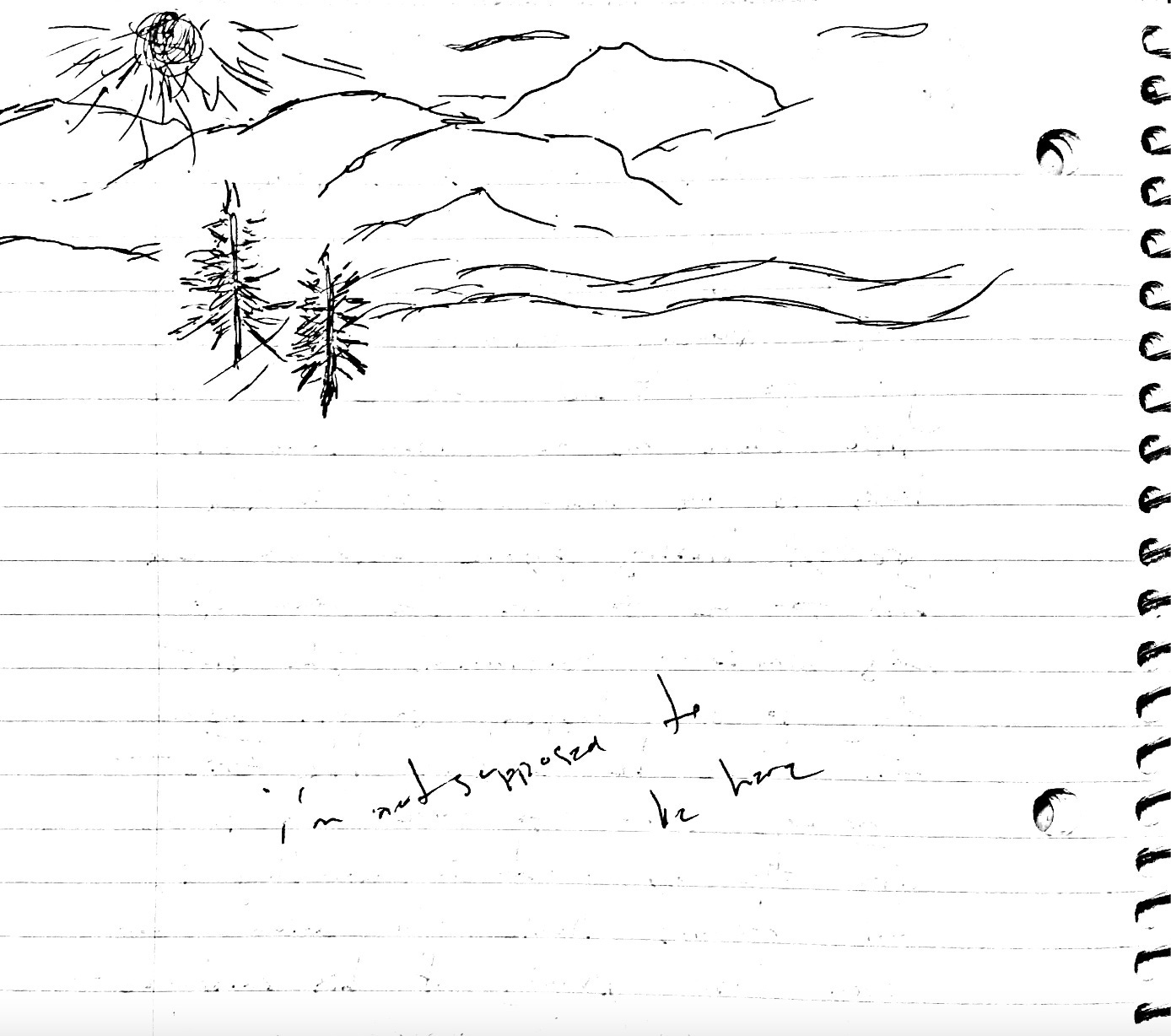

“My journal” led to scanned pages from a notebook, filled with her handwritten thoughts. These were unhinged scribblings, pictures of guns and cages and declarations of love for Columbine shooter Eric Harris, along with band logos and album covers for Smashing Pumpkins and Deftones. The name of her NeoCities handle, DissolvedGirl, was a reference to a song by British trip-hop group Massive Attack. One note simply read “Will I burn” four times in a row.

Another had what looked like a crude drawing of the mountains of Colorado, complete with a few scrubby pine trees, and the words “I’m not supposed to be here".”

An image of a bullet with the words “email me” linked through to the email secretsiaplos@gmail.com, her name backwards. Not exactly mathematician-level cryptography, but maybe a cry for help. I wondered as I sipped my third espresso of the morning. Did she want someone to find this and stop her? It certainly seemed like it.

I raced against hundreds of broadcast news producers around the country to find Sol. I pored through social media pages and property records, and I double- and triple-called likely contacts for her, trying to find something newsworthy, or someone who would tell me something that was.

In reporting on mass shootings, I’d begun to develop some personal theories about their origin. Only the greatest pedants will argue back if you say that they are almost entirely a male phenomenon. Typically, men exercise their anger by striking out at the world around them, while women strike inward. Some psychologists might tell you that it’s all about control.

A few academics think it’s rooted in the same sort of latent crowd revulsion that make George Romero–style zombie movies—featuring protagonists milling down surging crowds of human bodies in shopping malls and quaint suburban neighborhoods— so popular. With firearms easily at hand for so many, it seems inevitable that a few unstable individuals would be unable to resist the urge to lash out.

One passage of her online journal read the following:

“i wish i could distance myself from everybody in this f*cking world, as far away as possible from this poison that is the human race. i can’t stand anybody that surrounds me, i don’t wanna hear anymore human’s voices, only about 10 of them or less that i can stand to be around, but only one voice i truly want to hear every day and yet i can’t… life is merciless and i will always question why this universe decided to create humans.. ”

That didn’t sound far from the crowd revulsion mark. The “one voice” was presumably shooter Eric Harris, the subject of Pais’ infatuation.

But the distress etched out in the scanned diary pages seemed directed inwards. For all my academic theorizing, it didn’t help my current task, which was to find this girl, or at least figure out where she had gone.

The rest of the day went by without any success. The trail had gotten cold. It had been a frigid winter that year, and I stripped off my jacket as I rode home on the L train, packed like sardines in with the other commuters, my nose shoved so close to someone’s armpit I could smell their Old Spice. I fell asleep that night mousing over Sol Pais’s creepy website, clicking through empty spaces, trying to find another clue.

A Ghost in the Snow

The next day, the story lit up again. It was April 17th, three days till the Columbine shooting anniversary. We gathered around the blue glow of the DataMinr terminal.

Colorado authorities had identified the Uber drivers—the first who had picked her up from the airport and brought her to a mall with a gun shop in the suburb Littleton, and then the second driver who had picked her and her newly acquired pump-action shotgun up and brought her to the foot of Mt. Evans, one of the snowy South Park–style peaks that loom over Denver.

By now, the reports were flooding in. Some people said they’d seen her panhandling around Denver, one said they’d seen her outside of Columbine High School. The story was racing past us, and we were doing our best to keep up. Dozens of Colorado law enforcement officers were scouring near-freezing Mt. Evans for her. We were in action now, calling Public Information Officers, typing out our story, hovering our mouses over the “send” button.

A report flashed over Dataminr. “Woman seen running naked through snow on Mt. Evans.” Holy crap, I thought. It’s happening. Almost two thousand miles away in our Manhattan newsroom, our pulses thudded through the ceiling. What would happen? A firefight? Would she surrender? All bets were off.

Then, another flash on DataMinr. "There is no longer a threat to the community,” said the Colorado FBI. A quick succession of reports after that confirmed her death by gunshot. We filed our story, reporting her death. A letdown, we’d been beaten on every angle of the story, first by Twitter weirdos with frog avatars, and then by local reporters and law enforcement in Colorado.

That night I went to bed imagining the scene playing out on the darkness of my ceiling, in between the clanging of my ancient radiator. This girl running naked through the snow of Mt. Evans, dozens of bluff Colorado cops running after her, breath steaming in the cold. Then, what? An exchange of shots that left her dead? What had happened? What had brought her to Mt. Evans, rather than Columbine High School?

By the time the real story came out weeks later, the news cycle and my colleagues had all moved on to new gruesome crimes and celebrity misbehavior. An autopsy report said she’d been killed by a self-administered shotgun blast to the head. Clear Creek deputies had found her in a small clearing by a stump, the few possessions she’d brought with her all within arms reach.

But the fact that really burned into my mind was this: Sol Pais, the target of a national manhunt that had shuttered schools all around the state and opened old wounds, particularly for the people of Colorado, had been dead for days when the cops found her. She had ended her own life in the woods on April 15th, a day before the search started. Instead of going to school on April 15th, she’d hopped on a plane to Denver, Ubered to a gun shop and to the mountain, where she’d walked a few dozen meters into the woods and ended her own life, like a sick old cat that goes off alone to hide when it's time to die.

She’d been lying on the cold Colorado mountainside hours before her parents even reported her missing to local police on the 16th. She never even knew that anyone was looking for her.

For two days, we, law enforcement, and half the other breaking news reporters in America had been chasing a ghost, an image that I’m sure the gothy teen would have deeply appreciated. The report of the woman running naked through the snow is still strong in my mind, but I’ve come to learn that in breaking news situations, misinformation and confusion are commonplace, and you can’t believe everything you read. Almost every mass shooting I’ve ever covered where I spoke to eyewitnesses directly after the fact, someone would swear up and down that there were multiple shooters, which would ultimately bleed into the conspiracy-sphere.

Meditations on Violence

So where does that leave us all? Well, I’m no anthropologist, but maybe it says something about the breakdown of community and tight interpersonal relationships in our society, and maybe even the withdrawal of religion from public life, that someone like Sol Pais, sad and disconnected and looking for something to worship, ended up in a parasocial and slightly amorous projected relationship with two young monsters. If they’d made a different choice, Harris and Klebold would be in their early 40s now. Sol Pais would be 22, maybe finishing up her undergrad. Maybe she would have found her community in college, somewhere out of state, away from the sunny beaches and thudding nightclubs of Miami.

So what unifies Sol Pais with the killers she worshiped, and others she imitated? Well, perhaps it’s the desire to be known, and to feel connected. For people who are experiencing isolation, the internet allows them to connect with others along niche interests in a way that is unprecedented in human history. In the pseudo-religious fandom of these shooters, often referred to as “martyrs,” adherents are fiercely emotionally reinforcing of each other. Shooters who become part of their canon of “martyrs” are often the subjects of admiration and longing.

When you zoom out and look down at Sol Pais and her fellow Columbiners, you get the impression of a pseudo-religious death cult. One conclusion I draw, as my hair gets grayer and my low back stiffer, is that a lot of people are hardwired for religion. Religion is like social hierarchy: take it away from people and they naturally move to reform it. People without close connections or community are particularly drawn towards new movements, and the internet provides a way for them to find each other. Sol Pais’s mother told investigating detectives that her daughter had “no friends and usually stays at home."

Maybe Sol Pais was, as crude as it sounds, looking for attention. Or maybe she was seeking the same sort of religious adoration, a morbid and inverted version of the attention her classmates might have gotten for glamorous social media posts. When you look at the website she left behind, you get the distinct impression that she intended it to be found, that she wanted it to be looked at after she was dead. It feels like a meticulously crafted shrine to herself.

Since her death on April 15th 2019, someone, or perhaps multiple people, has been updating her website, adding new graphics and moving images and texts around. Her website even includes a guestbook, with hundreds of posts left by admirers over the years since she first made headlines. There’s even a subreddit dedicated to her, r/dissolvedgirl. And here I am, writing this substack post about her. She got her wish, it seems, embedding herself into the constellation of sad teenage suicides being worshipped and adored by confused kids all over the world. On the sketchy databases that we used to investigate cases like hers, it still says she’s alive.

Tough introspection. Thanks for digging for this perspective.

A journo friend on the schools beat once confided that the stories she hated / feared to cover were tragedies involving kids. We weren't much older than kids at the time. It's often too humbling to articulate.